Personal care and cosmetic products (PCCPs) are worldwide used products among all populations. And you are using them as well, right? Various studies have already emphasized the environmental and human health concern about the use of microplastics in PCCPs and since 2017, the European Union aims to restrict the intentional use of microplastics in those products.

This article briefly reviews the microplastics in PCCPs – to remind you on how you can minimize the global environmental issue of microplastics – every action counts!

Plastics facts

Today, plastics deliver numerous benefits to society and can be found almost everywhere around us. As a result of their versatile and attractive properties, plastics are being used in a wide range of consumer and industrial applications, like packaging, cars, paints, toys, etc. Plastic means durable, useful, lightweight, cheap, malleable, strong, and when thoughtfully used also recyclable and sustainable. We use plastic products to make our lives cleaner, safer, easier, and more comfortable. Plastics also drive innovations, facilitate resource efficiency, save lives in healthcare applications, create safety solutions, and have positive effects on climate protection. For example, plastic components in modern cars reduce their weights and emissions, lightweight plastics packaging reduces the amount of plastic waste, plastic insulations are more energy efficient…

“However, this valuable commodity has been the subject of increasing environmental concern. So, we can logically ask ourselves: Is plastic a boon or a bane?”

Here are some interesting data

Since large-scale production of synthetic materials began in the early 1950s, humans have generated 8.3 billion metric tonnes of plastics, a weight equivalent to 80 million blue whales or 1 billion elephants [1]. Over 300 million tons of plastic are produced every year and half of all is designed to be used only once [2]. In 2020, the European plastic industry employed close to 1.5 million people in around 52,000 companies, where the production reached 55 million tonnes compared to 367 mill tonnes of the global plastic production [3]. While some plastic waste is recycled (about 9%), the majority ends up in landfills and in environments where plastic material remains, accumulates, or breaks down into microparticles that pollute water and air, harm marine wildlife and can eventually be ingested by humans [1]. It is estimated that up to 10% of plastics produced end up in the oceans, where they may persist and accumulate, and accounts up to 80% of all marine litter [4].

“Do you think about the plastic’s fate in the environment, while you are shopping?”

From (macro)plastics to microplastics

In recent years, microplastics have been reported in diverse aquatic ecosystems, therefore increasing environmental concern about it was established worldwide. Microplastics are defined as man-made plastic items, solid synthetic polymers smaller than 5 mm [5], [6] that can be classified into primary and secondary microplastics according to their origin. Primary microplastics are plastic polymers that are produced in microscopic size and are commonly used for a variety of cleaning, polishing and scrubbing applications, like rinsed off cosmetics. On the other hand, secondary microplastics occur as a result of the decomposition of (macro)plastics or plastic waste in the environment due to various physicochemical or biological processes (e.g., UV radiation). You have probably seen discarded or deposited plastic bottles, packaging in the environment. A large part of the microplastic particles in the environment develops through the breakdown from bigger plastic items.

Primary microplastics can be unintentionally formed and released in the environment when larger pieces of plastics, like car tyres or synthetic textiles, abrase, wear and tear. On the other hand, microplastics are also intentionally added to a range of products including personal care and cosmetic products (PCCPs), fertilisers, plant protection products, household and industrial detergents, cleaning products, paints and products used in the oil and gas industry. We often don’t aware of primary microplastic presence in our daily habits. For example, it is estimated that tyres and synthetic textiles represent the majority of primary microplastics content in the oceans, 28% and 35%, respectively. To compare, microplastics from PCCPs contribute 2% of all primary microplastics in the oceans [1], [2].

Microplastics as microbeads

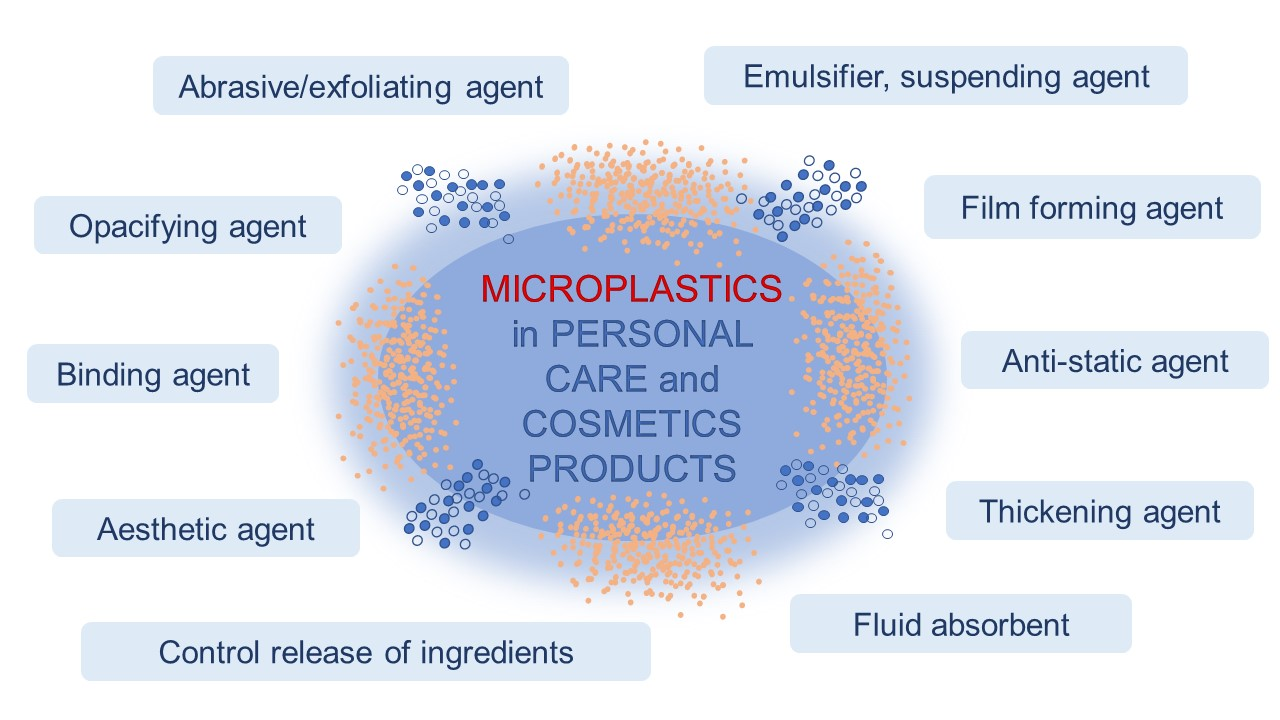

In PCCPs microplastic components are intentionally added with the aim to improve product characteristics. They are best known and used as abrasives, which are intended to remove dead skin and cleanse the skin [8]. They are also added as exfoliating, binding, suspending (emulsifier), film forming, thickening, aesthetic, opacifying or anti-static agents [7]. When used in PCCPs, microplastics are termed microbeads: those are tiny particles generally smaller than 1 mm in size. Microplastics in leave-on products, like lotions, make-up, deodorants, sunscreens, are usually even smaller, around micrometer to nanometer range [7].

“In some PCCPs, microplastics are intentionally added to ensure and improve a product function. We are often unaware of these chemicals, which means that we unintentionally contribute to the introduction of microplastics into the environment.”

Picture source: A. Bubik

Microbeads are very useful in rinsed off products. Based on the literature, polyethylene (PE), polyurethane (PU), polyacrylic acid (PA) can be very common constituents of various skin care and cleansing products, like hand cleanser, body and face scrubs, face masks [5]. Additionally, water-soluble polymers are also very often present in PCCPs, but they do not meet the criteria for the definition of microplastics and are therefore not included in the announced EU restrictions and bans in the field of intentionally added microplastics. In my opinion, many tasks are still open regarding synthetic materials in PCCPs.

GS tip: The handiest way to avoid microplastics in PCCPs is careful reading of product declarations, where you can easily recognize the presence of synthetic polymers.

Although the microbeads from PCCPs do not contribute with high percentages to the microplastic pollution, they can pose a threat to the environment. Therefore, we must be aware of the microplastics issue and prevent its global accumulation with all potentially hazardous consequences, most easily by avoiding the use of such products. In 2015, Cosmetics Europe recommended to its members to discontinue the use of plastic microbeads for cleansing and exfoliating purposes in wash-off PCCPs. It is great that they achieved 97,6% reduction of plastic microbeads today. This confirms the effectiveness of the voluntary initiative taken by this industry [9].

What are the main concerns?

Microplastics have a potential to cause harm to biota. Due to the small size, they are considered bioavailable to organisms throughout the food-web. Additionally, their composition and relatively large surface area make them prone to adhering aquatic pollutants. As a result, ingestion of microplastics may cause the toxin exposure and bioaccumulation through the food chain [10].

In 2017, the European Commission (EC) requested the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to assess the scientific evidence for taking regulatory action at the EU level on microplastics that are intentionally added to products. Afterwards, ECHA proposed a wide-ranging restriction on microplastics in products placed on the EU/EEA market to avoid or reduce their release to the environment. The proposal is expected to prevent the release of 500 000 tonnes of microplastics over 20 years [6].

What’s next?

Within the next articles, you will find out something more about the abrasives in cosmetics, water-soluble polymers, like polyethylene glycol (PEG) in your bathrooms. Additionally, don’t miss the Slovenian case study of microbeads in toothpastes.

- Abrasives in cosmetics

- Microplastics and PEGs

- Interview with Biochemist (microplastic)

- Microplastics in toothpastes – a study case

We believe that our information will make it easier for you to decide on the right, more environmentally and health-friendly purchase of PCCPs.

Sources

[1] How do microplastics affect? Iberdrola, S.A., Bilbao, Spain, 2018. https://www.iberdrola.com/environment/microplastics-threat-to-health

[2] Marine Plastics, Issues Brief; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland

Switzerland; May 2018. https://www.iucn.org/resources

[3] Plastics – the Facts 2020; Plastic Europe, Brussels, Belgium, 2021. https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2020/

[4] Revel, M., Chatel, A., Mouneyrac, C., Micro(nano)plastics: A threat to human health?, Environmental Science and Health, Vol.1, pp. 17-18, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2468584417300235

[5] Intentionally added microplastics in products, Final Report, European Commission (DG Environment), Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited, October 2017. https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/8ee3c69a-bccb-4f22-89ca-277e35de7c63/library/a40b7f19-2eec-40c0-b905-08e74efe7747

[6] European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), An agency of the European Union; Helsinki, Finland; https://echa.europa.eu/.

[7] Mahesh, B.P., Mukherjee, M., Yadav, K., Padhi, L., Personal (eco) care product: Microplastics in cosmetics. Toxics link for a toxics-free world, Vol.17, pp. 1-29, 2018. https://toxicslink.org/

[8] European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), Annex to the Annex xv restriction report, Proposal for a restriction. Helsinki, Finland, pp.148-149, 2019. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/05bd96e3-b969-0a7c-c6d0-441182893720

[9] Cosmetics Europe, The Personal Care Association; Brussels, Belgium. https://cosmeticseurope.eu/

[10] Guerrantia, C., Martellini, T., Perrac, G., Scopetanib, C., Cincinelliab, A., Microplastics in cosmetics: Environmental issues and needs for global bans, Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, Vol. 68, pp. 75-79, 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1382668918305635

0 Comments