Petra Ježeková is a graduate environmentalist and an eco-innovator, who dedicated her career to ecological cleaning with Živica organisation. She develops cleaning methods which protect the nature and health, even though they need more time and attention. She uses quality equipment such as bamboo and microfiber wipes and emphasizes the importance of temperature and modifying the eco-cleaning products to cleaning needs. Her work shows that ecological cleaning is possible, effective and necessary to protect our environment.

What does eco-friendly cleaning mean?

Petra: It’s an environmentally friendly clean-up. We try to cause as little damage to nature as possible and also to human health. However, it’s also a clean-up that takes a little longer than clean-up with regular products and procedures. People are impatient and think these products clean as well as the usual ones. They do clean well, but there are several factors to look out for.

The first is time – these products usually need more time to work. For example, when cleaning the toilet, I throw in an eco-tablet in the evening and clean it up in the morning to give it time to work.

Another factor is the use of high-quality mechanical tools. For example, there are various wipes – microphase, cellulose, and bamboo, with some of them we can clean completely without chemicals, and some can even be composted after the end of their lifespan. Microphase wipes are somewhat controversial because they are made of man-made fibre and release microplastics into the environment when they are washed.

With them, you need to consider their benefits, because they last for a very long time and can clean without chemicals. On the other hand, they are a burden on the environment when getting washed. They can already be replaced, in part, by finely woven bamboo towels. You need to move with the times, keep track of innovations and use what’s most environmentally friendly at the moment.

The third factor in eco-friendly cleaning is the effect of temperature. Eco-products sometimes need to be used in higher temperatures than normal products. For example, use warm or even hot water when cleaning.

The final factor is that if we want to reduce the use of chemical cleansers, we need to tailor the eco-friendly product. It’s different to wash clothes that are only slightly sweat-drenched or wash stains from food or grass. It is then necessary to add more of the active ingredient to the basic detergent – such as bile soap for organic stains or salt for stains of inorganic origin – and to prewash the stain. Regular wetting of laundry – i.e. exposure to temperature, time and medium – often helps too.

Where have your services been requested and how is it needed abroad?

Petra: It’s different in every country. It depends greatly on how informed society is. When we were doing a project on eco-cleaning and promoting it everywhere, more people and companies wanted it that way. When we offer this to companies today, some decide they want it, but without our direct supply, there is no demand.

I found only 3 eco-cleaning companies on the internet in Slovakia, but how busy they are with actual eco-cleaning, I can’t say. In Austria, which is a groundbreaker in this field, such services are being requested. I don’t know how it is anywhere else.

Another way to help this positive trend is to require eco-cleaning in public and state institutions through public procurement.

The situation has changed today, people want to live healthier lives. Do you notice that with companies and organizations as well?

Petra: I certainly have. I’ve worked in this field for 18 years and the situation has changed. We used to say very basic information to people. The bar is higher now, and the people are already better than us on some subjects if that’s what their heart is about.

Will you tell us what the Slovak legislation says about laundry detergents and cleaning products? (in a nutshell, stick out the essential information, hazardous substances, and safety data sheets)

Petra: Slovak legislation is already coordinated with the EU legislation on this subject. The most significant is a law from the year 2004 on the prohibition of phosphates in household laundry and cleaning products. More precisely, there’s some kind of maximum limit of 0.5 g (of the amount of phosphates in those products). It is not because phosphates are harmful to human health, but because their discharge caused over-fertilisation of the waters, so-called eutrophication, and consequently aquatic bloom, which causes problems for the animals living in these waters.

Another very significant piece of legislation is REACH, which foreshadowed the long struggle of organisations against chemical companies lobbying. It concerns the assessment, authorisation and admission of chemicals to the European market.

All hazardous substances should be banned based on the information we have about them today. They should not be used alone, in mixtures or as part of a formula. Legislation such as REACH is badly needed, as it also tests chemicals.

We also tested both common and eco-products in our cleansing project, which we selected at a drugstore by random selection. And what happened to us was that we got a call from terrified lab workers saying that when one of the regular cleaners was poured into the fish tank, they died almost immediately. So I believe, thanks to REACH, we don’t have chemicals like this here anymore. We need to monitor the development, substances, and product composition and prioritise ecological ones.

What about the WWTP (Wastewater Treatment Plants), do they manage to dispose of the substances? What about root cleaners or septic tanks?

Petra: WTPs can’t quite cope with all the normal cleansers. The problem, for example, is with the softeners. It is therefore a good idea to use cleansers in towns and rural areas, which are permitted for domestic root and bacterial treatment plants. In these cleansers, the composition is more closely monitored so that bacteria and plants can survive, making it more environmentally friendly.

What is the general health and environmental impact of substances in LCW (laundry, cleaning and washing detergents)?

Petra: This is very difficult to say because only individual substances are assessed and not their cumulative effect or different combinations and synergies. We inhale something, we eat something, we absorb something from our clothes through the skin, and we can’t judge everything that goes into our bodies in this way, and what it causes. That’s why it’s a good idea to use a minimum of these to avoid putting unnecessary strain on our bodies and our environment.

What’s the difference between an LCW for a “regular mortal” (a regular household), a company, restaurant or hotel?

Petra: Household products are not regulated in any way and we can use whatever we want – what we find on the market. And that’s why we can make the most of our choices here. Here we can avoid the unnecessary burden of chemistry.

In public spaces, everything is determined by the law. And while there, too, a way can be found to clean environmentally, it often ends in reluctance and lack of awareness among owners or cleaning companies. Our Austrian partner, “die Umweltberatung”, has done a major project in the past called “A household is not a surgery room” where he wanted to point out the futility and harmfulness of using disinfectant at home as well as its excessive use in medical facilities.

At the selected hospitals in Vienna, they cleaned everything except the surgery rooms with sanitisers, and this continued even post-testing. In fact, if sanitising is used excessively, even at home, bacteria and viruses become resistant and we cannot then remove them even when it is really needed (e.g. in the operating room), and it becomes necessary to look for and use increasingly aggressive means.

What about the people who work with these aggressive products? Do they know about the risk? Do they use protective gear?

Petra: The owner or operator is obliged to train the staff and provide them with all necessary aids. When we did the project, we saw that the cleaners had everything they needed – gloves, and masks. However, many of them did not use these aids because it was easier to clean without them. In short, the protective gear restricts them, they’re not used to it. But then, of course, they have health problems – eczema on their hands, difficulty breathing… especially if they clean with ordinary cleansers in some confined narrow spaces, such as bathrooms.

When we did this project at the Primate’s Palace in Bratislava, it turned out that when cleaners used only microphase wipes with water, without chemistry, to wash windows, they didn’t have eczema, even though they worked without gloves. Yes, it took them a little longer, but they were willing to take it when they saw the better state of their hands.

What about COVID? How do you feel about disinfectant on such a large scale?

Petra: It was a new situation. Everything that could be done as a precaution was done. However, even in this situation, over time it became apparent that quite common measures such as proper hand washing, consistent use of masks, regular and good ventilation and the like also helped. Therefore, there was no need, unless one had COVID, to sanitise everything.

Later, a variety of UV and ozone emitters were also used, replacing chemicals. In COVID hysteria, whole streets have also been sanitised somewhere, which of course also kills “friendly” bacteria, which we need and on many other microorganisms and animals, whether on our skin or around us, and also producing more and more resistant bacteria and viruses.

What does 15-30% anionic tensides and 5-15% non-ionic tensides mean?

Petra: People who care about eco-cleaning and health should read the composition of the products. But if they look at the label and they see 15-30% anionic tensides and 5-15% non-ionic tensides and the like, they don’t know what to imagine under that.

Tensides are a type of soap that relieves surface tension on a substance so that dirt can be coated by the soap and removed (author’s note; tensides are substances that have a purifying function and have different origins. They can be extracted from crude oil, but also from natural oils.). Even here, if we look in detail at the composition, e.g. in the Security Data Card (KBÚ in Slovak), we will see that for example, not all anionic tensides are friendly for us.

Therefore, it is necessary to request a KBÚ from the manufacturer or retailer, which they are obliged to provide to you, and in there you will find out all about what the product contains, how to handle it, what are the dangerous substances, how to correctly store it, etc.

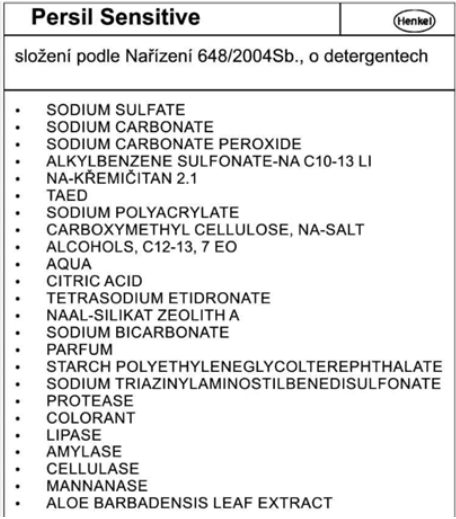

How can manufacturers only provide an abbreviated list of a product’s composition? e.g.: Persil: the formulation spelt out on the packaging: 5-15% anionic surfactants, oxygen-based bleaching agents, <5% non-ionic surfactants, polycarboxylates, phosphonates, zeolites, enzymes, optical brighteners, perfume.

And not:

Petra: There are several reasons. Some of the covers are very small, a lot of the text would have to be even smaller and it would be difficult to read. By law, the text has to be legible, so they can’t even put everything in there. Moreover, the law allows that everything does not even have to be there – “the manufacturer only has to state on the label the presence of enzymes, disinfectants, optical brighteners, perfumes and preservatives, according to the law”.

Besides, not enough people read it. When they did a survey in the EU, they found that very few people cared. Rather, they believe what they search on Google and what’s on the packaging. And of course, the manufacturers are also making excuses for the fact that this is their manufacturing secret, that they don’t want to put the exact composition there.

Consumers would have to put a lot of pressure on manufacturers to report all the information.

Why don’t “eco” brands name the full list of ingredients either? It is the same for cleaning or washing detergents. Do they fall under the same legislation?

Petra: Hard to say. They don’t have to, so they don’t. People don’t push it, so they have no real reason to do it. But what people often ask is why there are warning labels on eco-friendly products as well. This is because even an eco-friendly product can be irritating, corrosive, etc. It often has a high concentration of active ingredients, so that it is not diluted but compact, and therefore is dangerous.

For instance, highly concentrated vinegar for cleaning – 25%. You can’t work without gloves with it. Kitchen vinegar has 8%. Labels must be read there too, as well as following instructions and putting everything out of the reach of children and keeping it in original packaging to avoid using the wrong product.

For cosmetics, warning labels are less common, although they may contain the same substances, however, they are at a much lower concentration and so there is no danger. Citric acid, for example, is of food and non-food quality. Those for consumption must have higher purity and generally a lower concentration than those for cleaning. Other detergents, such as varnishes or hair dyes, have warning symbols, but they generally involve substances other than those used in the food industry.

What ingredients do you think would be sufficient for quality washing, cleaning and disinfecting?

Petra: It’s hard to say because, for everyone, clean clothes mean something else. Everyone has different standards of purity, whiteness, radiance and fragrance. Priorities need to be set. Do I want a healthier planet as well as my body or bright, nicely smelling clothes? For it cannot be achieved completely by the same eco-friendly washing as brightener powders and artificial fragrances. I, for one, advise people to be moderate. If they wash the eco 95% of the time, then they can afford to wash a few favourite pieces of clothing into the fluorescent light in the 5% ?.

When it comes to cleaning up, it’s a lot easier than washing. In this case, we can truly use only eco-products and what we normally have in the kitchen, such as lemon or citric acid, vinegar, sodium percarbonate, soap, borax and essential oils. All of these substances will be able to clean and disinfect the household to the extent needed. High-concentration alcohol and a smart sponge can be successfully used instead of chlorine for mould.

Something to finish – Your perspective, your opinion or recommendations for people/restaurants/hotels etc.

Petra: Eco-friendly cleaning is suitable for all, but it should be specifically taken care of by all those who have young children and animals at home who lick the surfaces and still touch them. Plus make use of high-quality mechanical aids and finely woven wipes.

In the area of eco-cleaning, conscious producers had tried for years before the ban to replace problematic substances and materials with others, being one step ahead of the competition while riding the eco-wave demanded by more and more customers. However, this must be monitored at all times.

Sometimes there’s a new substance that looks like it’s going to be eco and healthy for people, and after a few years of use, it turns out to be the opposite. This happened, for example, with octocrylene in sunscreen, when after a few years it turned out to be a hormonal disruptor. The eco-consumer must not be lazy and must look around. They may not know everything, but they may, for example, follow eco-labels or organizations that independently test and monitor products and learn from them.

Dosing is also an important thing in eco-cleaning. The dosage by the eye is always incorrect. We are wasting resources, and money and putting unnecessary strain on the environment with chemicals and packaging because we use up the cleaners more quickly. The correct dosage should be read on the packaging, use the measuring cup and follow the recommendations. In our project, the cleaning company saved up to 30% of the chemicals this way.

0 Comments